In Sapiens, Yuval Noah Harari argues that what separates humans from other species is not intelligence or tool use, but our ability to create and believe in shared stories. Money, nations, corporations, and laws exist only because enough people agree to act as if they are real.

Organizations are no different. They do not run on spreadsheets or org charts. They run on stories about what matters, what success looks like, and what is worth sacrificing for.

This is why strategy is not primarily an analytical function.

It is a narrative one.

Strategy Exists to Create Focus

At any given moment, a company could pursue a thousand different opportunities. It could frame its problems a thousand different ways. It could justify almost any initiative with the right metrics and language.

Strategy is the deliberate act of choosing one of those paths and ignoring the rest.

It is the act of saying this instead of that.

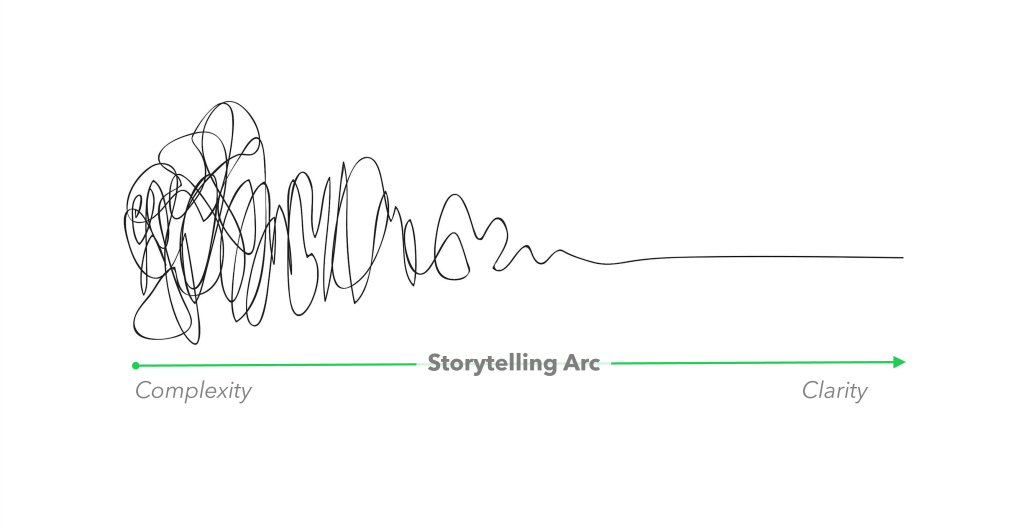

But focus cannot be imposed. It has to be understood. And understanding is created through stories. Stories are how humans compress complexity into meaning. They are how we decide what deserves attention and what can be safely ignored.

Without a story, strategy remains abstract.

With one, it becomes legible.

Strategy Without Execution is Just Opinion

Strategy that does not change behavior is not strategy.

Execution at scale depends on thousands of small decisions made by people who do not have access to the full context of the business. These decisions happen in meetings, inboxes, and production environments. They happen under time pressure and imperfect information.

Consistency under those conditions does not come from documents. It comes from shared meaning, which means strategy only works when it becomes a story that people can carry into their own work. A story that tells them what trade-offs are acceptable, what “good” looks like, and where effort should be concentrated.

Strategy has to Cascade

For this to work, strategy cannot live only at the top of the organization. It has to cascade — vertically and horizontally — from executives to managers to individual contributors, and across functions that experience the business in completely different ways.

A good strategy should be legible at every level:

- to the CEO setting priorities

- to the product team making design tradeoffs

- to the finance team approving spend

- to the intern deciding what “doing a good job” means

If a strategy cannot be translated into local action, it is not yet a strategy. It is a slogan.

The test of strategy is not whether it sounds coherent in a deck. It is whether it changes what people do when no one is watching.

What a Strategic Story Needs

Every effective strategic story contains three elements:

A foe — what we are up against

A future — who we are trying to become

A path — what we will do differently to get there

This is not the hero’s journey. It is not myth-making. It is a clear and compelling articulation of business logic: why this direction, why now, and why us.

Without a foe, strategy lacks urgency.

Without a future, it lacks aspiration.

Without a path, it lacks credibility.

When all three are present, strategy becomes something people can reason with — not just something they are told to follow.

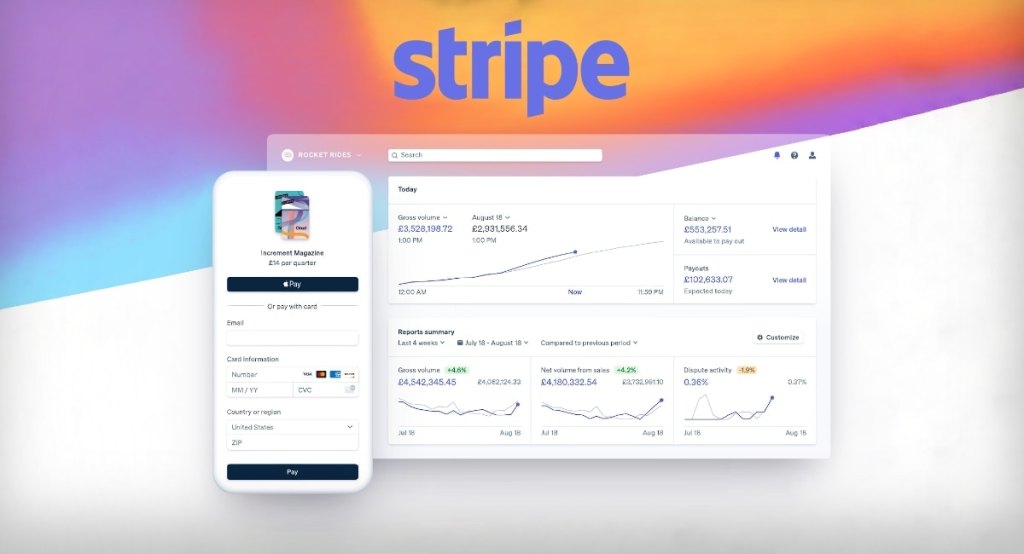

Stripe: Increasing the GDP of the Internet

Stripe did not frame its strategy as “build a better payments API.”

It framed it as a story: Increase the GDP of the internet.

This narrative did several things at once.

It defined a foe: economic friction for online businesses.

It defined a future: a world where anyone can start and scale an internet company.

It defined a path: remove complexity from payments, compliance, and financial operations.

That story gave coherence to decisions that might otherwise have looked scattered. Payments became billing. Billing became subscriptions. Subscriptions became tax, fraud, identity, and treasury. Each move could be justified not as product sprawl, but as another way of reducing friction to online commerce.

Engineers were not just shipping features. They were helping small companies participate in the global economy.

Leadership was not just expanding a platform. They were widening the surface area of what “the internet economy” could support.

The strategy did not live only in investor decks. It lived in product scope, hiring priorities, and technical ambition. It told people what problems were worth solving and which ones were distractions.

It was not a roadmap. It was a meaning-making device.

Unreasonable Hospitality

The best articulation of a simple strategy I have encountered comes from Will Guidara’s 2022 book Unreasonable Hospitality.

At the time, most fine dining restaurants were competing on what happened in the back of the house [kitchen]. More technique. More ingredients. More innovation behind the scenes.

Eleven Madison Park , Guidara’s restaurant, made a different choice. They decided their competitive advantage would come from the front of the house — from the experience of being a guest.

That choice became a story: unreasonable hospitality.

It told servers how far they should go to create delight.

It told managers what kinds of expenses were acceptable.

It told accounting why unusual bills would appear.

It gave everyone a shared mental model for what mattered. The strategy did not need to be explained in functional terms. It was already embedded in the language of the organization.

Up and down and across the business, the strategy was legible.

Not because it was detailed.

But because it was meaningful.

Story as an Operating System

Both Stripe and Unreasonable Hospitality illustrate the same principle: strategy is not what you plan to do. It is the story you tell about what matters.

That story does not replace analysis. It sits on top of it. It turns conclusions into commitments and priorities into behavior.

Organizations that execute well are not the ones with the most data. They are the ones with the clearest shared narrative about who they are and where they are going.

In that sense, strategy is not separate from culture.

It is culture, made explicit.

A company without a strategic story is a collection of functions pursuing local optima. A company with one has a chance of acting like a system.

Strategy as Narrative Infrastructure

We tend to think of storytelling as something reserved for marketing, branding, or leadership speeches. But strategy is where storytelling does the most work.

It is where a business decides:

- what it will optimize for

- what it will accept as cost

- what it will treat as noise

Those decisions cannot be made only with numbers. They require interpretation. And interpretation requires narrative.

Strategy, at its best, is the story that allows many people to make aligned decisions without being told what to do.

It is not about inspiration.

It is about coordination.

And in complex organizations, coordination is the hardest problem of all.