Strategy is very rarely linear. We seldom start at Point A, aim at Point B, and call it a day.

In fact, strategy is filled with randomness. Companies are complex adaptive systems sitting inside industries which behave in the same way.

The arenas in which companies compete are always changing. They are occasionally reflexive and never seem to tolerate a state of competitive equilibrium for too long.

Some arenas have a high degree of randomness, a situation that translates into a high degree of uncertainty when it comes to corporate planning. These are typically emerging industries or businesses that must contend with volatile external environments comprised of things like up-and-coming technologies or fleeting social trends.

Some arenas are more docile, providing higher levels of certainty and predictability. These tend to be mature industries with more commoditized products and services where the external environment remains relatively consistent.

The approach to strategy in each scenario differs.

The docile mature industry is more suited to what we know to be the typical corporate strategy processes of today. We can plan for the future because there is a higher degree of certainty. We can set a course for ‘how to win’ based on what we know to be true today and what we hypothesize will be true tomorrow.

But what if we have no idea what is true today, let alone what will be true tomorrow? What if the degree of randomness is so high, that it renders the typical planning process redundant.

That is where the optionality strategy comes into play.

Microsoft and AI

Another simple framework to think about strategy is as a series of bets made by a company with the intention of winning a market. There is no better case study on this front than Microsoft. The company has not only mastered the art of making bets, but has done so in an environment of cutting edge technologies which tend to have high degrees of uncertainty.

Via Matthew Ball speaking about Microsoft’s strategic approach to eventually monopolizing the Operating System market:

To manage uncertainty, Microsoft undertook a portfolio of bets throughout the 1980s and early 1990s that were often competitive with one another (or had competing premises) but collectively replicated the diversity, unpredictability, and dynamism of the market at large, thereby maximizing Microsoft’s odds of success in any future state. These bets were roughly as follows:

- Continue development of MS-DOS

- Collaborate with the many companies working on UNIX, namely through the ongoing development of its Xenix version of Unix (1980–89)

- Commence major investment(s) in Windows, a GUI OS (development started 1983, with Windows 1.0 shipping in 1985 and 3.0 in 1991)

- Form partnership with IBM to develop OS/2 (1985)

- Purchase 20% stake in Santa Cruz Operation, the largest seller of Unix systems on PCs (1989)

- Develop suite of applications (namely Microsoft Office, 1990–) that could operate across operating systems which Microsoft might have no ownership (or influence) over.

Their approach was not just a series of bets, but a series of parallel bets, mixing homegrown innovation, strategic partnerships, venture investments and alternative product development avenues.

Their motive: create optionality.

Microsoft also did this during the next major platform shift: the emergence of the internet.

Via Matthew Ball again: In 1995, Gates wrote his famous “Internet Tidal Wave memo… that led to a flood of investment in the company’s digital efforts:

- Internet Explorer (1995)

- MSN portal and search engine (1995)

- the $400 million acquisition of Hotmail (1997; $760MM in 2023 dollars)

- Messenger (1999)

- the company also remained diversified in its traditional OS bets, purchasing a 5% stake in Apple in 1997 for $150MM; the deal also involved Apple making Internet Explorer the Mac’s default browser).

And that brings us to the present day where they appear to be running the playbook again, this time with the current platform shift: the advancement in artificial intelligence.

- Microsoft spent significant sums acquiring companies in natural language processing (highlighted by a $19.7 billion purchase of Nuance Communications in 2021).

- The company has built out an internal research lab, with over 1,500 employees dedicated to developing AI in-house

- At the start of this year, Microsoft spent $10 billion to buy 49% of OpenAI, which gave them a large cut of OpenAI’s profits and broad rights to embed their technology into Microsoft’s offerings and product suite.

- The company also continues to build out its own proprietary GPT and LLM (large language model) that directly competes with OpenAI’s technology and could theoretically replace their tech at a lower rate of performance.

- Microsoft also continues to compete directly with OpenAI on other fronts, including pushing ChatGPT-powered Bing as an alternative to OpenAI’s ChatGPT consumer app.

- It is also opening up access to the Bing search database and making it available to other AI startups and companies to build on top of

- [And most recently, almost got away with the corporate steal of the century by hiring Sam Altman and his loyal OpenAI employee following]

This multi-pronged approach seems random. It casts a wide net… and that’s the point.

Consider the current state of #AI, its incredible pace of change and the competitive uncertainty that surround it.

Microsoft’s core strategic challenge with AI isn’t how they’re going to supercharge the Office suite or give Bing a new life and new personality. It is more high level. Microsoft’s core strategic challenge with AI is the high degree of competitive uncertainty it presents and the proposed solution is an optionality strategy.

The Optionality Strategy

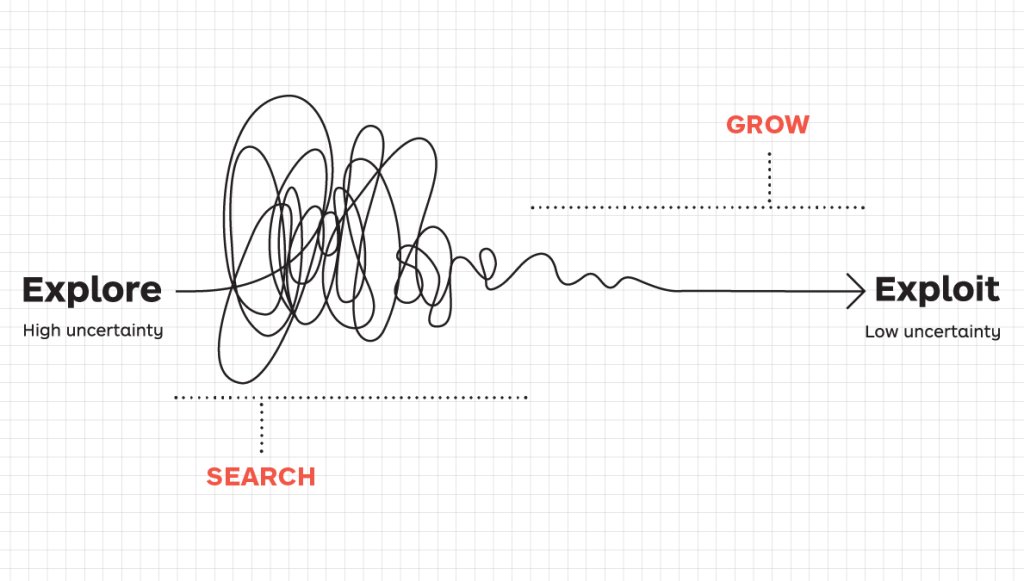

Defined in Roger Martin’s Play-to-Win terms, the optionality strategy is the pursuit of multiple approaches at the same time in cases for which the ‘where to play’ decision is clear, but how to win is not. The strategy is executed with the intention of building an understanding of the market, eliminating the uncertainty through targeted learning, and eventually/potentially making a decision on which bet to double down on.

There are bad times to pursue optionality. For instance, trying to be everything to everyone at the same time (which is a recipe for running out of focus, fast).

But there are good times to pursue it as well. Everyone from venture capitalists to single people dating follow the same logic. They pursue optionality when there is too much uncertainty, when there is still some ‘learning’ or ‘searching’ to do.

The approach also likely has a good shot at generating strategic alpha. That is, creating excess return from a strategy beyond exposure to the Rational Strategic Path—also known as the obvious strategic choice and default path everyone in the industry could take. In this case, the high degree of uncertainty of whatever is being pursued would suggest that it is off the rational strategic path and has not been explored by competitors yet (and if it has, try to leverage their learnings first).

An optionality strategy also sits counter to a traditional linear planning-based approach of defining a long-term vision and sticking too it. It counters the idea that the most important ingredient in a robust strategy is coherence. In fact, the optionality strategy sits on the opposite end of the spectrum from linear strategy.

Between the optionality strategy and more traditional linear strategy sits the zone of indecision. This is a halfway approach that lacks the positive coherence and alignment qualities of the linear approach and embraces the ‘many bets’ nature of the optionality strategy. This area is to be avoided and often leads to either strategies that are poorly defined or ‘everything’ strategies that refuse to make trade-off decisions.

There are also some requirements when it comes to the optionality strategy:

1/ It needs to be grounded in a ‘how to win’ decision: The point of an optionality strategy is not to endlessly explore or to test the waters in a new domain. It is done with competitive intention and with corporate learning in mind. It is oriented around figuring out how to win a market. This is not an innovation lab endlessly exploring, but rather a specific and intense effort to reach a goal or ambition. In the dating context, it is less Tinder or Bumble, more eHarmony or Hinge.

2/ It requires both resources and capital to survive: Unfortunately, this approach is likely not for everyone, at least not for domains where creating optionality has a high cost associated with it (due to the time, effort, resources or strategic investments that have to be contributed). Venture Capital investors have a war chest of resources to deploy in search of the one or two portfolio bets that are likely to represent the majority of their returns.

3/ Success will depend on managing the natural conflicts that will occur and on the judgement of the decision-makers: Multiple options means internally conflicting approaches might arise. Teams and strategic partners might be actively competing against one another and these conflicts require management in order to nurture the best bets to the finish line. That finish line will ultimately require the judgement of the corporate leaders to make the decision to maintain their portfolio of bets, or decide which path is worthy of doubling down on.

The judgement of the leadership group in charge is particularly important, because although the strategy is about eliminating uncertainty, it can never be fully removed. Decision-makers cannot work with perfect information because unfortunately there are competitors pursuing the same paths, and they exert pressure through the time decay of the option being pursued (more on that below).

But it is not just time that influences the value of the options that comprise an optionality strategy, there are other influences too.

How To Think About The Value of a Strategic Option

Pursuing a series of strategic bets is akin to holding a portfolio of call options. As such, you can understand the value of the strategy based on the general characteristics of options pricing. We won’t get into the specific maths of the Black-Scholes model, but looking at its component variables is a useful exercise:

The premium: This is the price paid for the right to the option: the price of admission, the entry fee. In finance, this is typically the price of the option itself. It is the $6.00 paid for next month’s at-the-money SPY contract. In strategy, the price you pay for an option has two primary components: it is both the capital/resources invested in the option’s pursuit, and it is also the opportunity cost of not pursuing the optimal path. What is the optimal path? Well, it cannot be known in advance. The optionality strategy is about spreading your bets out early on in order generate enough learning and information to understand the best path forward. Every dollar invested in an option off of the eventual optimal path is the cost (or premium) paid to execute the strategy.

Delta: Likely the most famous of the ‘Greeks’, Delta influences the value of the option based on the movement in the underlying security (or in this case, the underlying strategic path). As explained by Investopedia:

A good way to visualize delta is to think of a race track. The tires represent the delta, and the gas pedal represents the underlying price. Low delta options are like race cars with economy tires. They won’t get a lot of traction when you rapidly accelerate. On the other hand, high delta options are like drag racing tires. They provide a lot of traction when you step on the gas. Delta values closer to 1.00 or -1.00 provide the highest levels of traction.

On the strategy front, Delta provides us with a way to think about the option’s potential payoffs. If the strategic path works out, how valuable is that option? How big is the payoff relative to the premium? Was it worth the opportunity cost? How important is it to your how-to-win equation? Some paths might have an all-or-nothing outcome (high delta, likely high gamma—like Microsoft deciding to embed GPT into its Office Suite), and some might have a more narrow set of outcomes (low delta—like Microsoft building an internal AI research department).

Theta: This measures the rate of time decay in the value of an option. Time decay represents the erosion of an option’s value due to the passage of time. Most financial options come with an expiration date, and the closer to that date, the less valuable the option becomes. Strategic options have a less defined expiration date, but the reality of time decay is the same. The more time that passes, the more time your competitors have to jump out ahead as a first mover or snatch a strategic investment opportunity from your hands. Theta is always a negative factor and the sensitivity to time decay depends on how competitive a field is. As a general rule, the more competitive and fast paced the environment is, the more influence theta will have. If you establish that you are in a high theta situation, then you also must realize that every day longer that you pursue an optionality strategy, the lower the value of the options that you hold.

Explore vs Exploit

Eventually, the pursuit of an optionality strategy will lead to a decision point: should we continue to support our portfolio of bets, or should we double down on the option we think is most likely to be successful?

A good guiding principle here comes from the classic dilemma of explore versus exploit.

Exploration is gathering information. Exploitation is using the information you have to get a known good result.

We all face the explore vs exploit trade off everyday. Just think about how long you spent choosing a restaurant on your last vacation. Exploring options is helpful, but eventually, it becomes time to decide where to eat.

Decision theory runs deep on this topic and there are a variety of tools that can be used in deciding when to stop exploring and when to start exploiting. One example of such a tool is called the Gittens Index, which is a way to rank options based on their potential for future rewards while considering both the current knowledge about each option and the potential information gain from exploring new options.

I’ve asked ChatGPT to cook up a quick example of how this framework could be applied to the Optionality Strategy as we’ve defined it:

- Identify Your Series of Parallel Bets: Clearly define and separate the various strategies or bets you are considering for your business. Each bet could represent a different approach or orientation for winning the chosen market.

- Define Metrics for Success: Determine the metrics that matter most for your business success in the context of the chosen market. This could include factors like market penetration, customer satisfaction, revenue growth, etc.

- Initial Evaluation: Evaluate each parallel bet based on the available information and your initial assessment of their potential. This might involve analyzing market trends, assessing technical feasibility, or considering resource requirements.

- Apply the Gittins Index: Use the Gittins Index to calculate the potential value of each parallel bet by considering the current state of each bet, the expected future rewards, and the information gain from further exploration [mathematics withheld from the example].

- Update the Index: As you make progress or gather new information, update the Gittins Index for each bet. This ensures that the decision-making process is dynamic and responsive to changes in the business environment.

- Balancing Exploration and Exploitation: The Gittins Index will guide you in balancing exploration (trying out different strategies) and exploitation (focusing on the most promising strategy). Options with higher Gittins Index values are generally more attractive for exploration.

- Decision Point: Periodically reassess your options based on the Gittins Index. Once an option reaches a sufficiently high index value, it may be a signal to transition from exploration to exploitation, focusing resources on the strategy with the highest potential payoff.

While I’ve left off the math here for actually calculating the index values (that can be found here), the illustration is helpful in that it showcases a few key points about the strategy:

- Throughout the process, parallel bets should be tracked separately and remain distinct, or they risk entering the zone of indecision

- The decision-making process should be dynamic and respond to competitive and macroenvironmental changes, hence why bets should be evaluated continuously and the index should be constantly updated

- If a decision point of when to stop exploring is reached, it will come when the expected future state of the best bet outweighs the value of the information gain from further exploration of other options.

Unfortunately, the realities of the business world do not correspond well to the cut-and-dry nature of the world of mathematics. Decision points likely cannot be optimized or boiled down to a quantitative index score, but the logic that sits underneath the equations offer some helpful guideposts in strategic decision making: keep your bets distinct, continuously evaluate them, and compare them against the value of the information gain expected from exploring additional options.

Embrace a Learning Mindset

Sometimes, there will be no doubling down.

Learning is the key point of the Optionality Strategy. Learning also de-risks the next bet in the series.

Sometimes the series of parallel bets will simply evolve as a portfolio, with some bets being maintained, some new bets entering the fold, and some old bets fading away.

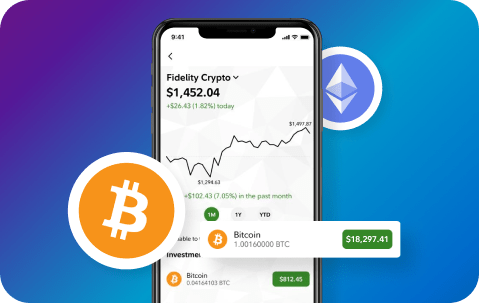

As another useful illustration of an optionality strategy at work, we can look at the way some giant financial services firms are also approaching digital assets today. No company has done this better than Fidelity.

Here is their rough timeline and series of bets:

- Bitcoin mining commences (2014)

- Blockchain incubator formed (2015)

- Incorporate digital assets into the Fidelity.com experience, first by allowing clients to view their external digital asset balances (2017)

- Avon Ventures launches to focus on deploying capital into blockchain and crypto start-ups (2018)

- Fidelity Digital Assets receives NY Trust Charter and launches, offering custody and trading services to institutional clients (2019)

- Fidelity Investments (Canada) launches the Fidelity Advantage Bitcoin ETF (2021)

- Fidelity Crypto launches, offering retail investors a service to buy and sell digital assets commission-free (2022)

Crypto is to financial services what AI is to Microsoft. A series of parallel bets can help a company understand a new technology while also spreading out their risk of moving too late or moving too early. Fidelity started simply with mining, then formed a research team, then began to integrate digital asset touchpoints into the client experience, then started investing capital into projects, and now have launched a full suite of institutional and retail products and services across multiple geographies.

Almost the entire portfolio of bets is still intact. One path may eventually pay off more than the others. But the important point is that Fidelity successfully leveraged optionality for corporate learning and used that knowledge to de-risk their entry into the digital asset arena.

We Could All Use a Little Optionality

Doesn’t it feel like the world is moving faster than ever before?

We’re all operating in what seem like accelerating levels of uncertainty.

The optionality strategy provides us with an approach to alleviate some of that uncertainty.

Ironically, for many of us (Microsoft and Fidelity included), creating optionality is the easy part.

The hard part starts when you begin to make choices and manage your series of parallel bets like a portfolio. It is hard to sell your losers, but it is even harder to ride your winners. Every investor will tell you that.

But what every investor might not tell you is what they learned from each of their bets. Without learning, the optionality strategy is just a catch-all approach to the market.

Learning helps us de-risk. It is the solution to the problem of uncertainty… and we could all use a little bit of that in our lives these days.