Minimum viable products…

MVPs were all the rage back in 2012 when we first started exploring the fintech arena at the consultancy I worked at.

Eric Ries had just published his book and validated learning was being discussed in the offices of both corporations and startups alike.

The framework was elegant. Build-measure-learn: a concise feedback loop to be executed in the simplest way possible in order to help a start-up discover the right thing to build.

The ethos encouraged rapid experimentation over elaborate planning: Get an MVP to market as fast as possible and then to use customer feedback to iterate in short cycles.

There was no long-term objective, just a hypothesis and customer-guided development/validation.

The approach was received with great fanfare by big name advocates like the founders of Dropbox, Marc Andreessen and Steve Blank.

But, at the same time, the framework seemed to stand in stark contrast with the real-world corporate strategy work our firm was a part of. This involved helping companies take a long-term view, understand and select the arena they wanted to compete in, and develop unique insights and a compelling approach for how to win the market.

There was no rapid iteration taking place here, no agile methodology, just plain old-fashioned planning and execution. This approach was also underpinned by the theories put forward by some big names in Corporate Strategy like the Michael Porters and Peter Druckers of the world. It is also encapsulated well by the famous Steve Jobs quote:

Some people say give the customers what they want, but that’s not my approach. Our job is to figure out what they’re going to want before they do.

Let’s just say Steve was not doing much validated learning at Apple. It was intuition over intellect.

So which approach to strategy and building is more correct: long-term top-down, or short-term customer-directed? Or… is there a way to take the best of both worlds and combine the two into a hybrid approach? The following is a framework that attempts to do just that, applying the validated learning (build-measure-learn) process to traditional strategy work.

BUILD

The Structure of a Strategy

In preparation for this post, I stumbled across The Outthinkers podcast hosted by Kaihan Krippendorff. In it, Kaihan likes to ask each of his guests a question: What does strategy mean to you? While I haven’t gotten through all the episodes, the variety in answers and approaches suggests that there is not a common understanding of the word. It is situational and context-dependent.

The definition I like to lean on is hybrid mix between two of the leading management thinkers of our time.

Strategy is Problem Solving: Richard Rumelt, author of Good Strategy, Bad Strategy, defines strategy in terms of problem solving. The term “strategy” should mean a cohesive response to an important challenge. Unlike a stand-alone decision or a goal, a strategy is a coherent set of analyses, concepts, policies, arguments, and actions that respond to a high-stakes challenge. You need a strategy when you have an opponent or a difficulty standing in the way of your ambitions. If there is no challenge or problem to solve, then there is no need for a strategy. Richard’s follow-on book, The Crux, is focused squarely on this idea.

Strategy is Decision Making: Roger Martin, of the now-famous Playing to Win framework, looks at strategy in terms of making choices. Strategy is an integrated set of choices that uniquely positions the firm in its industry so as to create sustainable advantage and superior value relative to the competition. A choice to serve everyone, everywhere is a losing choice. There are infinite directions that a company could pursue and strategy is about focusing on selecting a path forward that is both value creating (what most firms do well) and positions the company to win in its chosen market (what most firms forget to do).

Funny enough, on different occasions, the two pros have discussed the other’s approach.

Martin agrees, strategy should be a problem-solving technique. It should be oriented at closing the gap between our ambitions and our outcomes.

Rumelt agrees that strategists are decision makers, and if you conceive of strategy as decision making, then your job would be to examine each alternative and select the best one.

To bring the two together, we can say strategy encompasses both approaches. It is defining a problem set around which to orient decision-making:

Strategy is overcoming an identified obstacle by making an integrative set of choices that best positions a company to have a sustainable competitive advantage.

For many start-ups (particularly those who are pre-revenue), their primary identified obstacle is overcoming uncertainty around product-market fit. This is where the lean start-up framework makes a lot of sense because it helps solve the primary problem. However, it might also fall short in that product-market fit doesn’t guarantee the creation of a competitive advantage. Taking another perspective, a start-up’s primary challenge might simply be defined as ‘survival’ and the lean start-up framework provides the quickest first-step in getting to the next round of funding.

At the other end of the spectrum, top-down strategic planning at large corporations often focuses too much on competitive advantage and the path forward, but it can often fail to adequately direct attention on a core problem to solve. This can lead to a strategy that is full of good ideas, but has insufficient emphasis on the set of activities that will best close the gap between ambition and outcome.

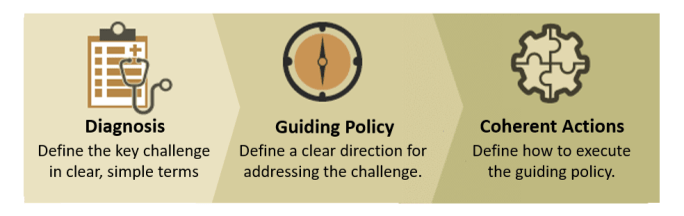

In terms of strategy development and articulation, we can use Rumelt’s framework with one small tweak. A strategy consists of a:

- Diagnosis: working out where you are and framing the challenge around how to win.

- Guiding policy: the overarching approach to solving the challenge.

- Coherent action: a comprehensive, cohesive plan to reach your goal.

Nvidia provides an excellent example borrowed here from YouExec:

- Diagnosis: 3D-graphics chips will become the primary chip used in the future of computing and the first mover would have a significant competitive advantage.

- Guiding policy: Shift from a holistic multi-media approach to a sharp focus on improved graphics for PCs through the development of superior graphics processing units (GPUs).

- Coherent Actions: 1) Establish three separate development teams; 2) Reduce the chance of delays in production/design by investing heavily in specific design simulation processes; 3) reduce process delays involving the lack of control over driver production, by developing a unified driver architecture (UDA).

Defining strategy in terms of both problem solving and subsequent decision-making forms a path to the first step in how to put strategy into practice in something we can call the Strategy Value Chain.

The Strategy Value Chain: An Organizing Framework for Implementation

Just like a value chain brings a product or service from conception, through the different phases of production, to delivery to final consumers, a strategy value chain performs a similar act. It creates, puts into production, and executes (delivers) a strategy through an organization.

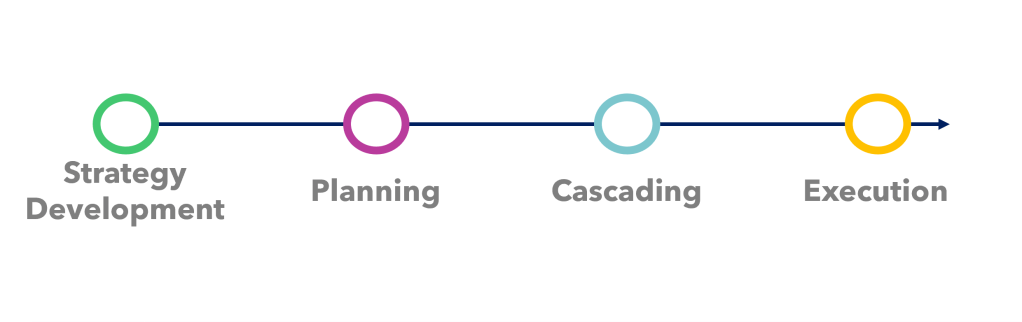

It consists of four primary components:

1. Strategy Development (why we should pursue a strategic direction) – the conception of a strategy, which involves the elements above: the diagnosis of a problem and a guiding policy to address it.

2. Planning (how we pursue the direction chosen) – this is the production of strategy, where a set of coherent actions is mapped out at a high level that align with the guiding policy. This step is typically executed by corporate strategy groups and/or executive teams.

3. Cascading (what do these actions mean for each department of the company): with coherence as an objective, this is how strategy filters across an organization through the initiative mapping of individual departments. Given the corporate objectives, this is how individual divisions/departments align their course of action.

4. Execution (following through on the plan): this step creates forward motion and puts the strategy into action on the ground. This is where the rubber hits the road and each department does the actual work to deliver the product or service.

MEASURE

The Need for Agility: Hypothesizing About the Future

Strategy is ultimately a creative act. It is both a craft and an artform.

The challenge with creative acts is that they are subject to judgement and interpretation. What looks like an elegant strategy to one person might look like a horrible idea to another. Not only that, the environment a strategy exists in is dynamic. Between wars, a global pandemic and the rapid adoption of LLMs, the past few years have illustrated the high degree of uncertainty that all businesses face.

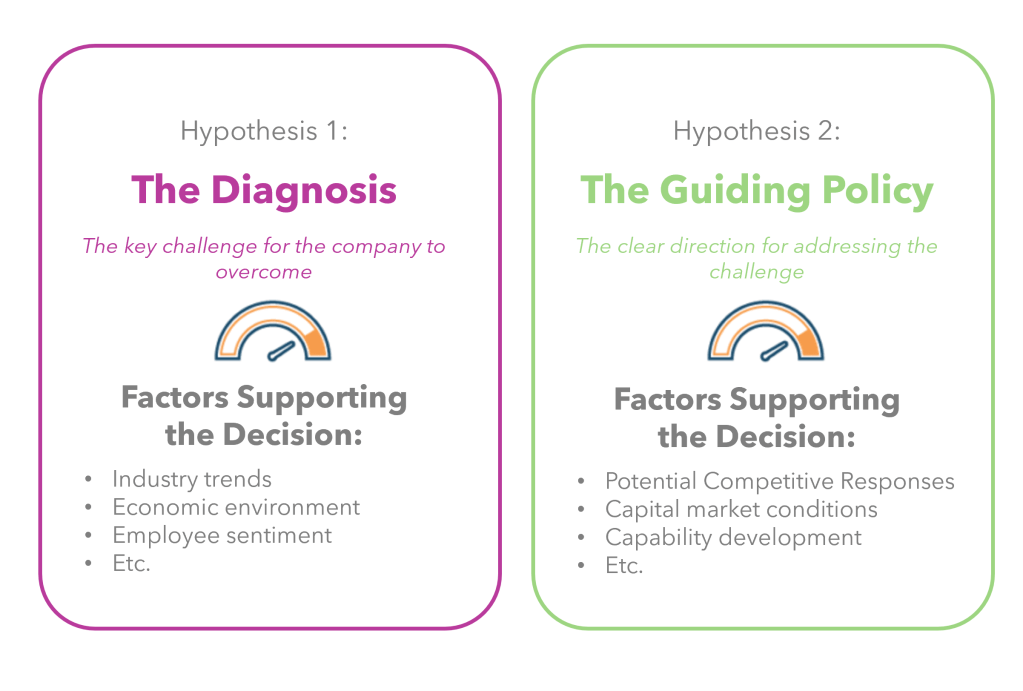

Starting at the top of the Strategy Value Chain, there are two parts of the Strategy Development process that require a notable amount of judgement: diagnosis and guiding policy formation.

Diagnosis (aka, the problem): A diagnosis requires a hypothesis that the challenge the firm selected is indeed the most important issue to solve. This step in strategy development is quite rare, albeit essential. Often, aspirations like “our strategy is to become the market leader” or “our strategy is to double our revenue in five years” are substituted for a true diagnosis. If this statement doesn’t answer the question what is holding us back from reaching our aspirations, then not enough specificity has been achieved in identifying a core problem to solve.

Guiding Policy (aka, the solution): A guiding policy requires a hypothesis that the proposed approach will indeed make progress against the diagnosis and will move the company toward its ambitions. Companies may not be good at diagnoses, but they tend to spend a lot of energy coming up with a guiding policy. However, sometimes this can be mistaken for defining a company’s mission and vision, which are useful exercises, but are too broad for strategy. Nike’s mission is to bring inspiration and innovation to every athlete in the world, but that is not their strategy. The guiding policy must answer the question, if this policy successfully guides our actions, will the result be a solution to the diagnosis above?

Both steps are decisions where choices must be made against a backdrop of uncertainty.

We cannot rely solely on analysis alone to guide these decisions. Strategy is often labelled as an analytical exercise, but as Roger Martin likes to say, analysis depends on data, and all data comes from the past, so unless we expect the future to look exactly like the past, then analysis is an overrated strategic act.

So, we must rely on the judgement of people within the business. This is where domain expertise, competitive intelligence, industry research, and other forms of understanding come into play. We do this work, often at a single point in the year, to ensure our hypotheses are as well-informed as possible, taking account of the most up-to-date information about the current situation.

This is also why executives (particularly, chief executives) are often seen as the strategy decision-makers. They are theoretically in the role that should have the best and most complete set of information in the company, and as such, the individual in that chair should also possess the best judgement based on their experience, domain expertise and skillset.

Then a decision is made… and this is where most Strategy Development works stops and things advance to the Planning, Cascading, and Execution stages.

Unfortunately, the challenge with this is that the circumstances around which our hypotheses are based on is constantly changing. The information available today to make a strategic decision might be completely different than if we were to do the same information gathering exercise a month from now. Some broad categories of that inform our hypotheses include:

- The position of competitors

- The response of competitors

- New entrants

- Encroaching substitute products

- Expanding platforms and network-based businesses

- Horizontal integration by adjacent industries

- Vertical integration by suppliers

- Emerging suppliers/vendors

- Emerging strategic partners

- Industry life cycle state

- Emergent technologies

- Scaling technologies

- Technology adoption

- Cultural norms

- Social trends

- Age distribution

- Socioeconomic distribution

- Population growth

- Health and safety

- Natural disasters / pandemics

- Environmental factors

- Sustainability

- Shifts in law

- Evolving in regulation

- Changes in policy

- Political party in power

- Collective action

- Geopolitical conflict

- Foreign/trade policies

- Economic growth

- Inflation

- Interest rate environment

- Capital market environment

- Employment and labour market trends

- Consumer behaviour

- Customer needs/wants/jobs-to-be-done

- Customer satisfaction

- Customer buying habits

- Distribution channel reach

- Marketing awareness and reach

- Brand perception

- Value perception

- Organizational structure

- Company financial position/strength

- Internal capabilities/investment

- Employee morale

- Company culture

- Etc…

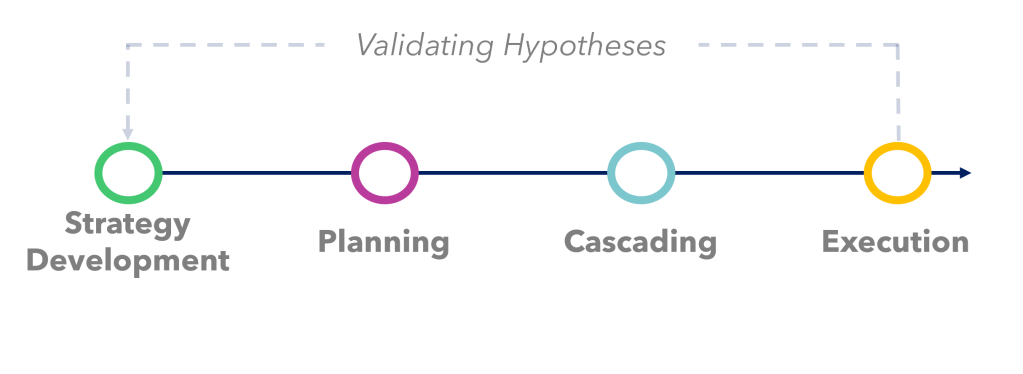

We like to think ‘x’ is the most important strategic problem to solve, and ‘y’ guiding policy will best address it. But this could change at a moment’s notice due to one of the factors above… so effective strategy should act to constantly validate these hypotheses.

LEARN

Validating the Hypothesis

Most companies gather a lot of information and data upfront to inform their strategy and then continue to gather, analyze and benchmark as time goes on. But what is this activity for? For it to be productive, it must be aimed at more than just tracking results (which is usually the primary motive). It must also be aimed at validating the assumptions underneath the two major strategy hypotheses: diagnosis and guiding policies.

Like the lean start-up framework, this helps us to know when to pivot ‘strategy’. Many organizations Build Strategy, then Measure results, but they stop short of the Learn stage. We need to be deliberately looking for signal that our hypotheses are correct, much like a start-up looks for a signal that they have found product-market fit.

How can this be done? If strategy development follows the steps of defining the Problem and Solution as above, then applying this validated learning skeleton to the strategy process can seek to validate both of these choices by asking the questions below:

1/ Validate the Problem: What do we believe to be true about our circumstances today that creates the opportunity we’re focused on?

2/ Validate the Solution: What would have to be true for us to succeed in executing against that opportunity?

Both of these questions seek to confirm or deny the assumptions that went into selecting the strategic challenge the company faces (if one was selected, at all) and the corresponding solution. This is also the fifth step in the Strategy Value Chain:

Validation (ensuring the plan continues to focus on the right things): This is the work required to continuously validate the assumptions that went into the Strategy Development phase to ensure that they are still firm strategic ground to stand on.

To drill down further, the following additional set of questions can provide the analysis needed to understand what has changed:

- What factors did we consider in making our diagnosis?

- Which factors received the greatest weight in that decision?

- How have those factors changed since the initial decision point?

- What assumptions did we make along the way?

- What unknown unknowns have emerged since then?

If anything has changed from the previous analysis, it is important to understand their implications and consider whether the path chosen still makes sense, or whether a pivot in strategy may be required.

In the language of validated learning, this is equivalent to innovation accounting:

- First, define a baseline by establishing your strategy and collect real data on where the company is right now.

- Second, attempt to tune the engine from the baseline toward your ambitions by validating your hypotheses and iterating making adjustments to the strategy as needed

- Third, decide, pivot or persevere: does the data tell you that your actions are moving you toward your ambition or is a reworking of either the Diagnosis or Guiding Policy required.

This type of validation can occur on a periodic or continuous basis. Regardless of frequency, it is again left up to the judgement of decision-makers as to what actions to take, if any. It should also be noted that ‘doing nothing’ is also a choice that can have consequences, despite inertia always pulling us in that direction.

The point here is that strategy work does not just end after a direction has been set. It is a continuous process that requires monitoring progress toward a company’s aspiration AS WELL AS monitoring the underlying assumptions for change. The former without the latter is incomplete. It is an odometer without a compass: like measuring the distance a ship has travelled without checking that it is indeed going in the right direction!

Strategy is Not Static

Any strategy is backed by an aspiration that requires a set of attributes to be true. But what if one or more of those attributes is no longer true? That all but guarantees a gap will open up between a strategy’s aspirations and its outcomes. Applying a validated learning approach to strategy development and execution can help to prevent that gap from getting too wide before it’s too late to pivot.

Strategy is a continuous process, not an annual exercise. The firms that can recognize this will be better equipped to keep pace in today’s rapidly evolving world.