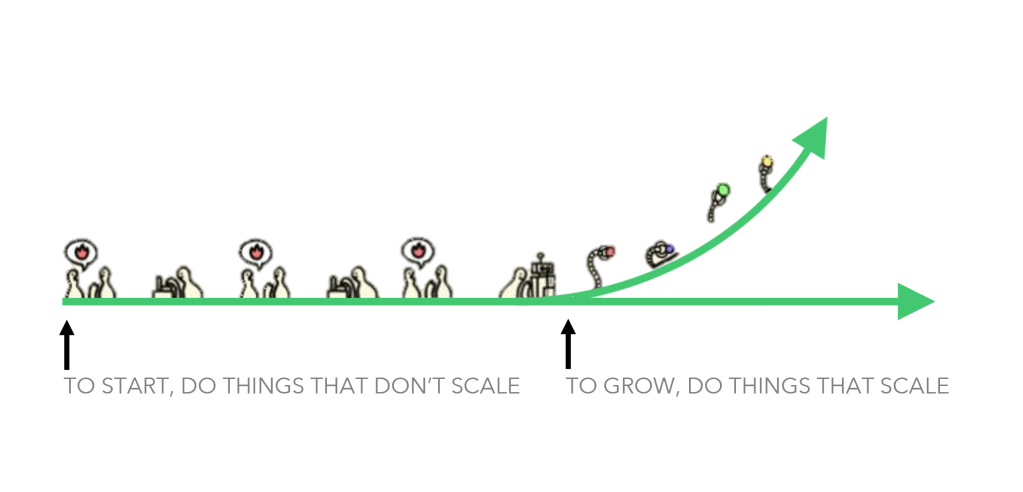

“Do things that don’t scale”.

This common advice, often bestowed upon start-up founders—particularly those going through Y Combinator—was popularized by Paul Graham in a 2013 blog post.

The crux of his argument was that a start-up’s biggest advantage is its speed and ability to adapt and what better way to learn what customers want then to recruit and service them individually, one-by-one.

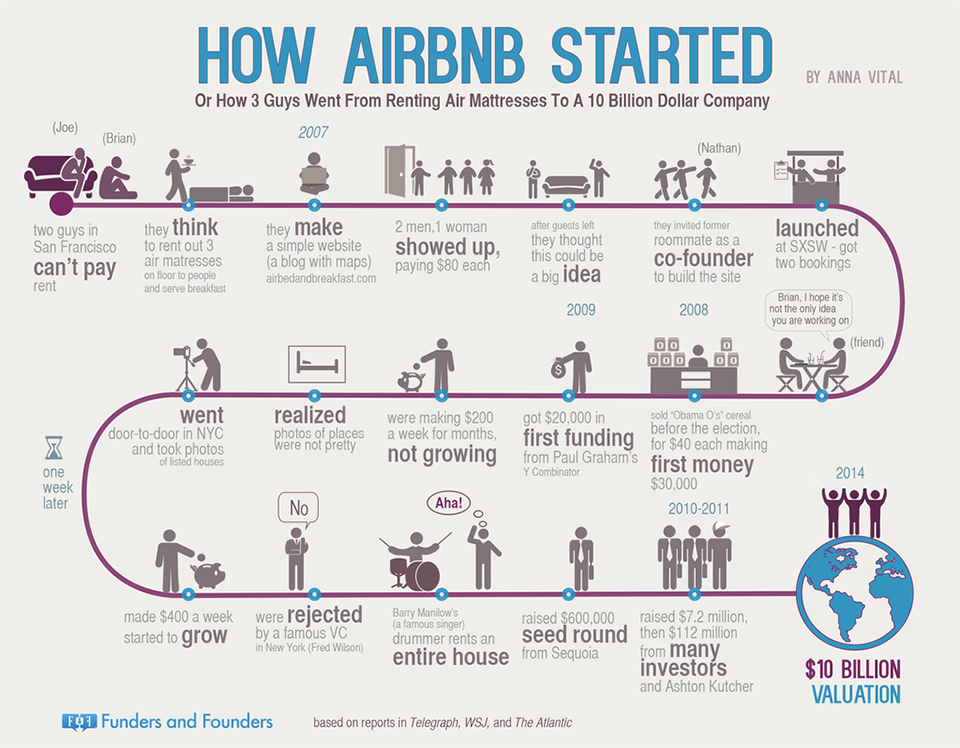

The ultimate example of this playbook was executed by Airbnb:

Marketplaces are so hard to get rolling, and in Airbnb’s case, their non-scalable techniques consisted of going door to door in New York, recruiting new users and helping existing ones improve their listings. CEO Brian Chesky even talks about showing up at early customers’ doorsteps to help them photograph their recently listed accommodations.

Here’s a podcast for more on that story:

This not only gave Airbnb primary knowledge of the needs and perceptions of their initial customers, it also helped them lay the first brick in what would eventually become a sturdy economic moat. Not only that, the path Airbnb pursued was hard to replicate by their competitors given its manual and resource intensive-nature providing the young company with solid competitive footing as it matured.

Competitive Advantage in Fragmented Markets

Zooming out for a second, the primary function of any business is to connect supply with demand. Companies can do this in two ways:

- Through supply chains (ie. Restaurants connecting hungry customers with a meal)

- Through networks (ie. Instagram connecting creators with their audiences).

Supply Chains

In the supply chain world, supply is often centralized at the point of distribution. Retailers, for example, create storefronts packaging up the supply of various goods and delivering them to customers through single points of distribution. As another example, banks package up their financial products across a number of verticals and deliver them to customers in a single interface.

Plainly stated: producers create products and services and package them up for consumption further down the chain. In this world, those closest to the customer often tend to hold most of the most Power in the chain and can often create a competitive advantage through that strategic positioning.

Networks

A networked world, however, is different. Networks tend to bring together fragmented supply and demand to connect on their own accord: a two-sided marketplace. The value network builders create is in the volume and quality of these connections. However, the challenge that they all face, is that of fragmentation.

Early on, Airbnb had to solve for this: Their approach was to shrink their unit of focus. Instead of aiming at global domination and rounding up dormant rental space across the world, they instead focused on the smallest possible unit. Starting with a single neighborhood in a single city, they proceeded listing-by-listing, doing things that didn’t scale to get the flywheel churning. Then, they shifted to move city-by-city, and eventually, were able to reach the size necessary to become a global operation.

Early on, Airbnb concentrated their non-scalable resources on specific focal points, allowing them to aggregate fragmented supply (vacant rooms), connect that with specific demand (travelers looking to find accommodations in that city) and build out a local network effect business first, before expanding more broadly.

Uber also followed this tactic. They rolled out city-by-city, establishing a strong local market presence in each area code before moving on to the next. One locale at a time, Uber would invade with a strong ground game, talking up local governments, recruiting drivers, and building out a brand presence that almost singlehandedly created the ‘ride-hailing’ category.

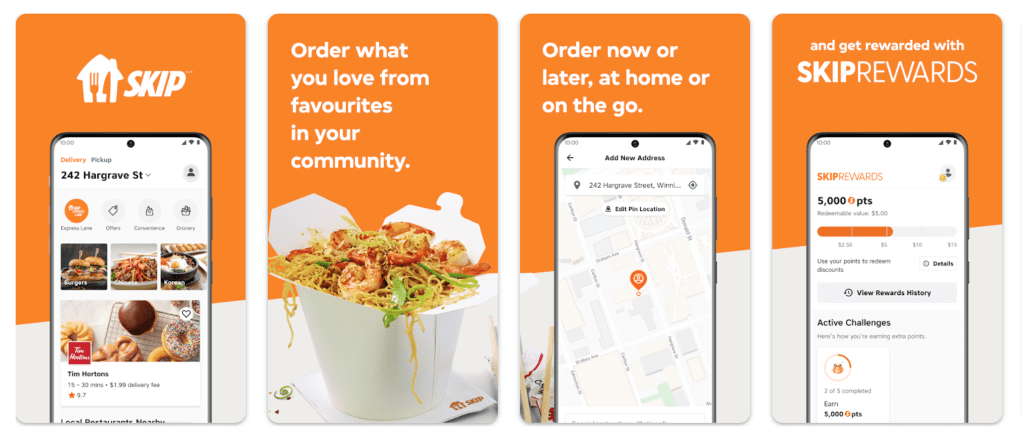

Similar stories exist in the food delivery service market, where Postmates, DoorDash, GrubHub (and here in Canada, SkipTheDishes) ran similar races, albeit three-sided, and in a slightly different fashion.

The common things that unite these gig economy companies: they were able to successfully unlock dormant supply in a fragmented market in order to create a competitive advantage, and often did so at the local level first, by doing things that don’t scale.

Unlocking Dormant Supply: Harnessing the Seven Powers

Why is unlocking dormant supply a competitive advantage? In short, because it creates what Hamilton Helmer refers to as POWER.

To oversimplify, Power is the set of conditions that create the potential for persistent differential returns. It consists of two attributes:

- Benefit (Magnitude of Power). The conditions created by Power must materially augment cash flow. It must both create value and capture value.

- Barrier (Duration of Power). There must be a persistence to the creation and capture of value. That is, there must be some aspect of the Power conditions which prevent existing and potential competitors from competing and arbitraging the profit pools created.

Hamilton also defines strategy in his framework:

Strategy: a route to continuing Power in significant markets.

I’m here to argue that AirBnb, Uber and other sharing economy businesses created a templated and repeatable strategy on their path to Power. The template is as follows:

- The ‘Do Things That Don’t Scale’ Strategy: Do things that don’t scale in order to build a two-sided marketplace that unlocks dormant supply and provides the business with the benefits of network economies and cornered resources.

- Benefit: An economic moat is produced by a superior value proposition (eg. more choices of places to stay) or pricing (eg. cheaper accommodations than hotels), where the fragmented supply (eg. spare beds/places) that is unlocked creates never-before-seen choice, convenience and/or access for customers.

- Barrier: Doing things that don’t scale to build network economies creates a process that is both manual and time consuming for competitors to replicate and is also subject to a first-mover advantage where network-based businesses often become winner-take-all markets because of the network effect they create.

This template is most easily illustrated through the sharing economy, but its potential competitive applications extend beyond.

Beyond the Sharing Economy

The circumstances that produce the conditions for Power through the ‘Doing Things That Don’t Scale’ strategy are threefold:

- an existing mature market, with;

- fragmented supply, of a;

- commoditized resource

Although success has mostly been found in physical markets, the strategy can be applied to any business or industry where the circumstances above exist.

For example, what could this look like in financial services? There are already some examples that exist where companies are borrowing from the template above:

- Capital: Capital is a commoditized resource and the capital markets are literally a giant fragmented mechanism for allocating it efficiently. Crowdfunding platforms and peer-to-peer lenders both have attempted to follow the path of centralizing capital demand and supply into a network effects business.

- Alternative Investment Assets: There are a number of businesses that have contributed to the ‘financialization of everything’ trend that persists in the fintech world today. Rally (collectible cars), Vinovest (fine wines) and Masterworks (art) all attempt in some way to harness some form of ‘fragmented’ supply of an asset and deliver it to consumer in a platform-style business.

- Buy Now Pay Later: This one is a little harder to see, but even BNPL companies follow this template. The fragmented supply of the commoditized asset they aggregate are retailer discounts—those discounts are a surplus that is shared between the consumer (via an interest free loan) and the BNPL provider (via fees) in order to help the retailer drive value through higher conversion rates.

But why have none of these businesses become a household name as familiar as Uber or Airbnb? Because they failed to ‘do things that don’t scale’ and create the economic moat necessary to become a large platform. That, or the market they were pursuing was too small…

But there is another commoditized resource that has some underappreciated potential in the financial world.

The Power of Points

Loyalty rewards are magic in financial services.

In a world of little differentiation and static customer relationships, rewards programs provide a differentiator, incentive mechanism and path to customer acquisition and retention, all in one! Cash back, points, prizes… whatever the case, loyalty points are a fungible commoditized resource that have been around since the 1980s (a mature market) and have birthed a cottage industry of points enthusiasts on the lookout for the best offers.

Also, because you tend to earn points in most programs across total spend (ie. at all businesses), they have a fragmented supply. People pick them up slowly over time at various merchants and vendors.

An existing mature market, with fragmented supply, of a commoditized resource: a perfect scenario for the Doing Things That Don’t Scale Strategy to be tested.

Case Study: Introducing Neo Financial

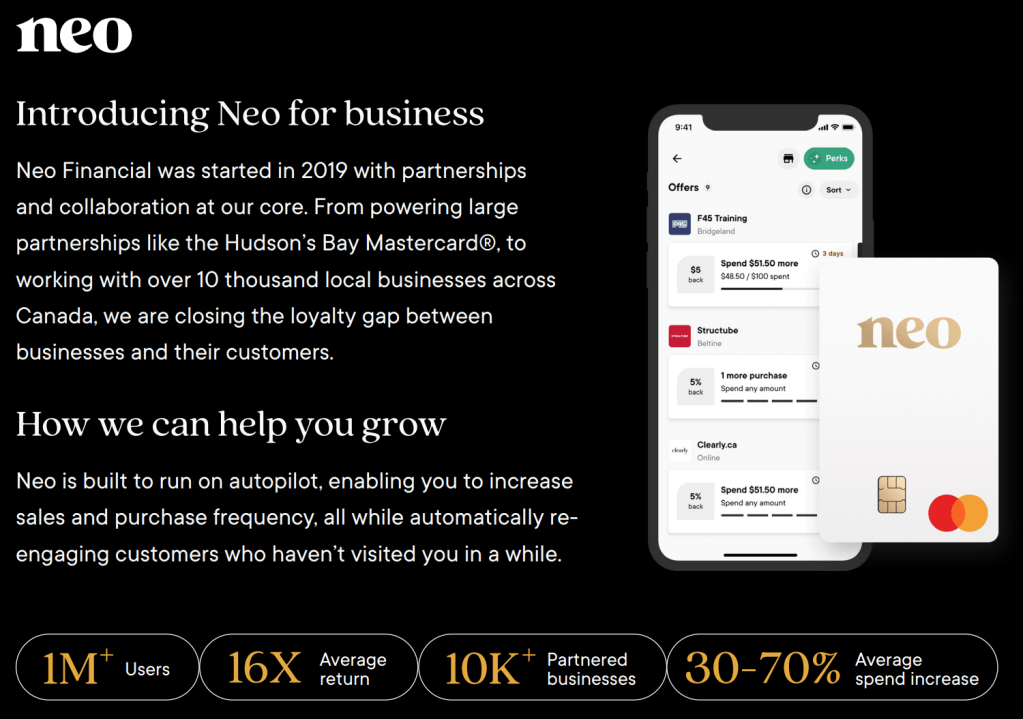

As chance would have it, some seasoned entrepreneurs have already spotted this opportunity: enter Neo Financial. Neo describes themselves as a leading Canadian financial technology company that provides a modern, streamlined financial experience for consumers and businesses. Their suite of customer products consists of a credit card, savings account, investments, and mortgages and the firm works with large enterprises and local retailers through a B2B shelf with options around embedded finance, co-brands, and loyalty tools like the rewards network and the Neo Store.

The rewards network plays a key role in the company’s strategy. Neo has already added more than 10,000 partners to their cashback rewards network, ranging from national brands like Harry Rosen and Endy down to local favorites like Balzac’s Coffee Roasters and Craft Beer Market.

Here’s a description of the approach in a recent Financial Post article:

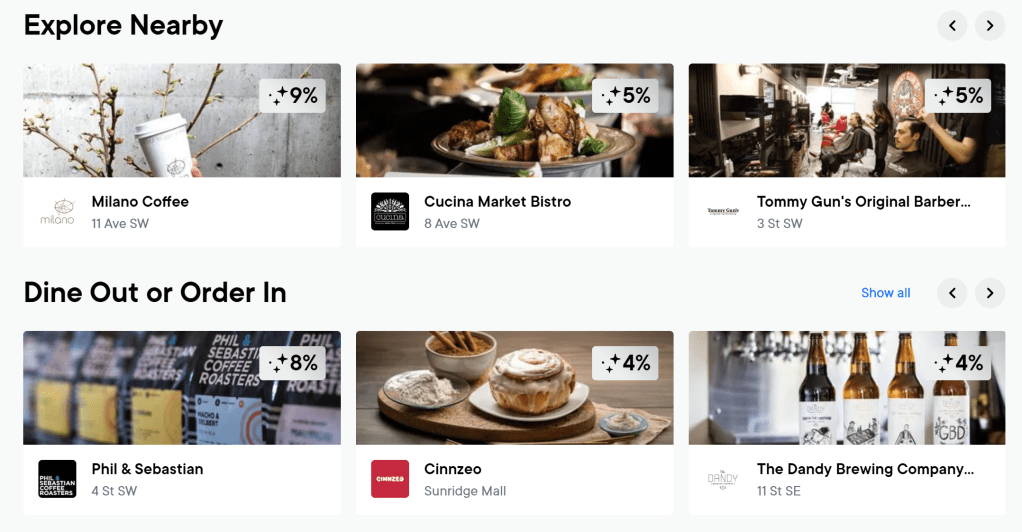

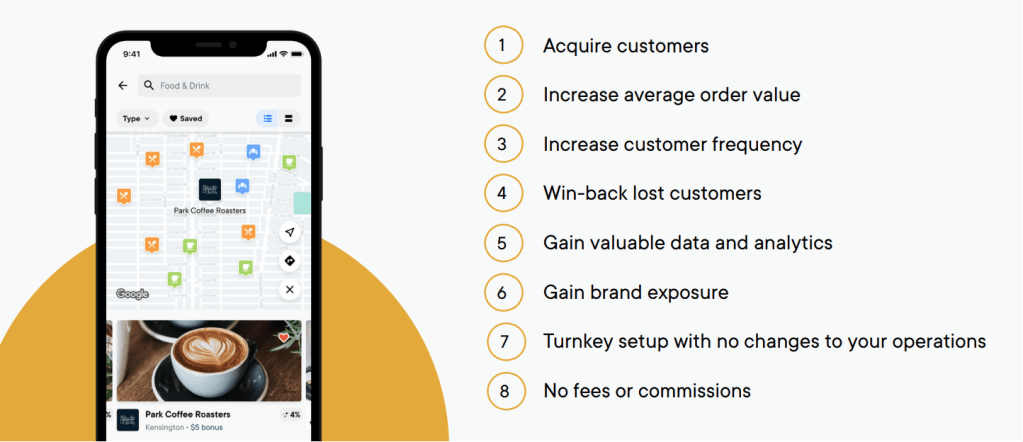

The Neo app enables Canadians to explore businesses on the rewards network with a live map feature or search by category to discover the cashback they can earn. When paying with their Neo Credit card or Neo MoneyTM card, customers receive unlimited instant cashback from these businesses. This dynamic network drives Canadians to spend at these partners, giving all businesses access to loyalty tools traditionally reserved for only the biggest brands. These tools are critical in helping small businesses acquire and retain customers.

The key highlight of the approach is Neo’s focus on small businesses. Why have small businesses traditionally been excluded from having access to loyalty incentives like larger brands? Because doing so is a highly manual process, signing up businesses one-by-one. In other words, it would require a lot of grunt work that doesn’t scale!

The story of Neo Financial started in 2020 when the company launched, building out a consumer value proposition that involved acquiring new users by offering above market interest rates on their savings account and below-market fees on their credit card. This was step one: use a compelling value proposition to build one side of the marketplace.

In tandem, Neo started going door-to-door in Calgary, the city where the company is headquartered, adding small establishments to their loyalty program. That program started offering incentives (via Neo cashback rewards) to customers on the platform and created proof points for more merchants to sign-up… and eventually, after a herculean sales effort, escape velocity was reached. Take a tour of the city of Calgary today and visit some local coffee shops or restaurants and you’ll quickly start to notice a sticker in the window of A LOT of establishments. Neo’s ground game is strong!

Their value proposition for small (and large) businesses who lack a loyalty program is incredibly compelling:

Neo also strategically focused on Western Canadian markets, out of sight, and out of mind for a lot of their big bank competitors based in Toronto. They appeared to build things out one city at a time, growing the number of merchants on the platform and creating a flywheel where the more merchants they added, the more compelling their rewards program became to their users. All of this is now protected by a moat, doing things that didn’t scale, like going door-to-door across local small businesses to get the flywheel started.

I haven’t spoken with the founders, but to an outside observer, this sounds very familiar. As an fyi, the founding team at Neo are the same people who launched and scaled SkipTheDishes (a food delivery service similar to DoorDash) across the country:

SkipTheDishes was founded in 2012 with the idea of creating a more efficient online food ordering and delivery network… As the company scaled between 2013 and 2016, the co-founders launched SkipTheDishes in many Canadian cities, initially focusing on mid-market cities, including Burnaby, East Vancouver, Calgary, Edmonton, Red Deer, Prince Albert, Grande Prairie, Regina, Saskatoon, Winnipeg, Mississauga, Etobicoke, Kitchener/Waterloo, and Ottawa (Source: Wikipedia).

Back to the definition of the strategy we’ve mapped out: Do things that don’t scale in order to build a two-sided marketplace that unlocks dormant supply and provides the business with the benefits of network economies and cornered resources.

This was the playbook at SkipTheDishes, which led to a $200 million exit. This also appears to be the playbook at the team’s encore act at Neo Financial.

The beautiful thing about the strategy: it is incredibly challenging to replicate. Not only does it require a lot of time and resources, but as stated earlier, two-sided marketplace businesses tend to have winner-take-all characteristics where first movers tend to have an advantage.

Conclusion

“Do things that don’t scale”: it is incredibly common advice for start-ups and mature businesses alike. But few companies have successfully taken that tagline and turned it into a competitive advantage that can be used to outmaneuver competitors.

Airbnb, Uber and perhaps we can soon add Neo Financial to that list.

Incredibly savvy strategy – kudos to the team!

(NOTE: I have not spoken to anyone at Neo Financial while writing this. I am certain the strategy and approach is more nuanced than I have outlined here. This is simply the perspective of an outside observer who has publicly available resources at their disposal. Any feedback and/or corrections would be welcomed.)