In financial markets, when asset prices get pushed off their natural state of equilibrium for an extended period of time, this state is known as a ‘dislocation’.

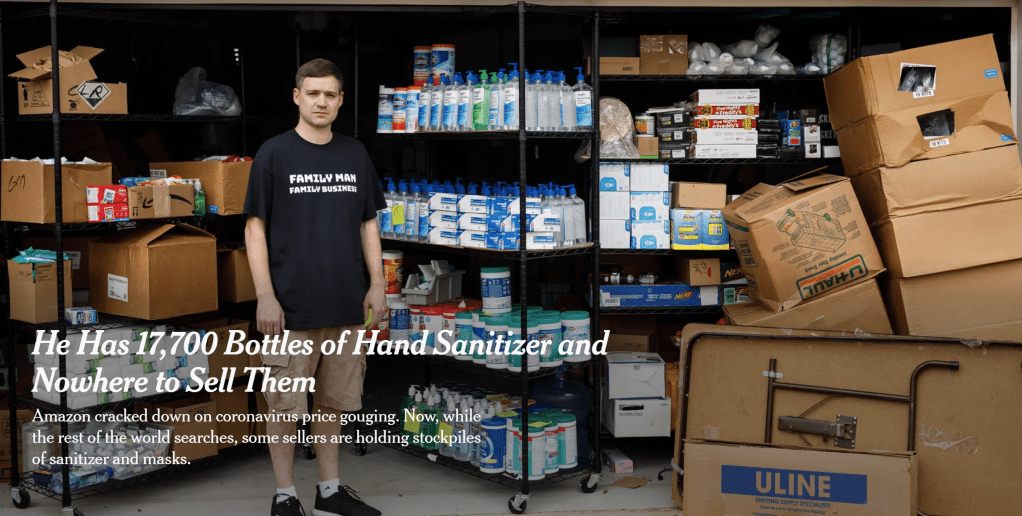

Looking back, the panic that set-in on March 2020 after we collectively realized a pandemic was upon us produced a dislocation across capital markets. The shutdown of supply chains and corresponding increase in inflation produced a dislocation in the economy. These macro dislocations caused micro dislocations, opening up opportunity and mispricing in assets ranging from a barrel of oil (which went negative for a period of time) to cleaning products (remember the guy below?).

But as this headline from Barclay’s reminds us, “market dislocations create opportunities for investors”.

More broadly, this phenomenon does not just apply to financial markets, it applies to ALL markets.

Without dislocation, there is no opportunity, there is only competition.

When there is no dislocation, the efficiency of markets and the competitive nature of capitalism make any opportunity an uphill battle.

Arbitrageurs iron out mispricings and other industry peers will iron out competitive advantage.

So, what makes for an attractive market?

Good strategy requires reading and responding to situations where the market gets pushed off its natural state of equilibrium, creating a gap (or mispricing) that needs to be filled.

- When new advancements in large language models (LLMs) were made broadly available via OpenAI and others, a technology gap was created and a new crop of start-ups was born to fill it by embedding LLM capabilities into every imaginable digital tool.

- When consumers got used to slick digital experiences, but few existed in the financial services industry, a gap slowly opened up and a wave of fintech start-ups from neobanks to robo-advisors rushed in to take advantage.

- Even when passive investing was academically established to carry certain benefits over active investing, the burgeoning ETF industry emerged to fill the void.

As the examples suggest, dislocations can emerge from a new technology, from shifting consumer preferences, or even from the academic world.

More generally, dislocations come from the external environment, outside the walls of the individual company: political/regulatory change, social shifts, technological advancement, economic disruptions, and environmental crises to name a few big categories.

Dislocations can also be macro or micro. They can extend globally, like a pandemic or interest rate shock. Or they can be isolated locally, like a change to a city by-law or a discovery that metadata can be attached to an individual Satoshi, creating inscriptions and ‘Bitcoin NFTs’.

Dislocations can also be abrupt, or a slow burn. They can happen suddenly, like when Russia invaded Ukraine, or they can happen slowly over time, like when an aging population and immigration policy changes create shifts in demand for certain products and services.

In a hypothetical world where the external environment never changes, competition becomes driven by internal factors. Who has the lowest price, the best economies of scale, the greatest network effect, the most competitive acquisition offer? Eventually, competition nets-out and every customer won is a customer taken from someone else.

Dislocations are what create opportunity in the marketplace.

They are what produce strategic alpha.

And at the end of the day, isn’t that what we are all chasing?